In 2017 — the 50th anniversary of the modestly named Summer of Love — Researchers from the Department of Psychiatry, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics at Zurich University determined that LSD can turn a common event into a game-changing sacred experience. This heightened transformation in meaning takes place due to the stimulation of certain serotonin receptors not only during an acid trip, but after — in-other-words, with LSD, personal change could be ongoing and permanent. This wasn’t exactly news to acidheads.

I had my first Lysergic acid diethylamide’s experience in 1966, dancing with a six-foot tall tiki-head in Crazy Daisy’s Hollywood courtyard. Between giggles and offerings of acid to her Māori friend, Daisy chanted, “Acid is concentrated life. Acid is concentrated life.” The Māori nodded yes. I laughed thinking “concentrated life” sounded like a brand of detergent. An awakening of colors. Brighter brights. Whiter whites. Bluer blues. Lightning bolts struck the swimming pool. I walked the deck of a briganteen, watched a witch consumed in flames, discussed Plato’s Allegory of the Cave with a giant Porky Pig policeman, and was convinced — before finally touching down at sunrise — I saw the interconnectedness of all things. I became other. The moment was sacred. Acid is, afterall, a disruptive agent.

People don’t want other people to get high,” Kesey said, “because if you get high, you might see the falsity of the fabric of the society we live in.

Earlier on this altered February 1966 day, author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and LSD ethusiast, Ken Kesey, had driven his psychedelic school bus past my home in the San Fernando Valley. Kesey was heading from San Francisco and points north to the onion-shaped Unitarian Universalist Church I occasionally attended. There, he would lead a mind-altering congregational happening.

“People don’t want other people to get high,” Kesey said, “because if you get high, you might see the falsity of the fabric of the society we live in.” Daisy and I loved to tear fabric and the weft and warp of Kesey’s perspective captivated us. We wanted to stretch our consciousness. While Kennedy talked of spacesuits on the moon, psychotropics became our Apollo program.

First consumed in 1943, scientists dropped it, armies dropped it, psychologists dropped it, movies stars dropped it, commoners dropped it, and by the Spring of 1966 I dropped it. By then, it was already christened a dangerous hallucinogenic and declared officially illegal in California. My high broke the law. The people who outlawed LSD weren’t in-tune with Kesey. They didn’t believe it exposed falsities in the fabric. They believed it shredded the fabric. LSD changed perception, they claimed, by ripping apart the work ethic and dissolving values. Its victims allegedly burned flags, stared at the sun, and jumped off skyscrapers.

At any rate, a culture woven from General Motors, General Electric, Dow Chemical, and corporate Christianity — cars, power, synthetics, and meta-metaphysics — was disrupted by an LSD-laced demographic enthralled by the counterculture memes of Kerouac, Ginsburg, Burroughs, and other Aquarian hallucinators.

By June of 1967, Daisy and I had revisioned our sense of meaning in Los Angeles’ gothic canyons and valleys of enlightenment. We heard the prophecies of Aldous Huxley floating over the Easter Love-In in Griffith Park, death in Vietnam on our TVs, and The Doors at the Whiskey. In the cowboy hills of Chatsworth, we saw Charles Manson waiting in the wings. We knew we were blessed and doomed. It was the perfect time for catharsis. On June 21, 1967, Daisy and I followed the trails of Kesey 400 miles north along the coast to San Francisco.

No self-respecting participant in that Haight-Ashbury summer was a ‘hippie.’

Let me be clear: No self-respecting participant in that Haight-Ashbury summer was a “hippie.” Unexpected aberrations of nature; abnormalities to families and friends; post-beat-Nuremburg Trial, atomic bomb-raised, Disney-informed, motion-pictured coded, stardust and golden detached and hyphenated teens in a moment of imagined solidarity, we were… maybe. It was said our greeting was a sign for nuclear disarmament; our farewell, a psychedelic mushroom cloud of dreams. It was said, we danced to the delirious precision of circumstance hoping to drive out the money lenders and strip Pilate of power by the will of our drug-enhanced exhuberance.

Some believed that LSD was — a pathway to the sacred spiritual power of divine grace, a cathartic union with God. But God isn’t that simple. Some think their thoughts of God are reality, in the same way that some think that their thoughts on acid are. But, like LSD, God is a chemical response. A simulacra. We’re not flying. We’re not seeing Jesus on the cross. We’re not experiencing the meaning of life. We’re just high.

That we w’re a birth spike is immaterial. Baby Boomers are numerous, but not monolithic. Yet, covered by the gawking press, our youth became “The Summer of Love” — the first mass-marketed American social experiment. Love was the brand, psychedelia the style, and disruption the drive.

It was the summer Hendrix ignited his guitar while Mohammed Ali refused to be drafted; the summer Janis Joplin played the Fillmore, stoned, while Jane Mansfield died in a car crash, beheaded; the summer we mourned Coltrane while Roxbury, Durham, Memphis, and Detroit burned; the summer we watched 45,000 more U.S. troops go to Vietnam while H. Rap Brown pronounce violence “as American as cherry pie.”

In a twenty-first century tribal act of artificial purification, we found the “falsity in the fabric” and, in an eternal return to endless creation grew to become the fabric: lawyers, doctors, cooks, philosophers, alcoholics, janitors, political operatives, junkies, generals, hair stylists, microbiologists, Steve Jobs, and Donald Trump.

On one hand, the Summer of ‘67 became the wellspring of western degeneracy, on the other, the zenith of romantic idealism.

The truth is, the Summer of ‘67 is neither. It a figment of serotonin receptors. It’ s a hoax. A hallucination. Fake news. “To hell with facts,” Ken Kesey said. We need stories.”

The story of that summer ended on October 6,1967, when a coffin was carried through Haight-Ashbury commemorating the death of the “hippie.” But nothing died. Love is not all you need. Violence is still as American as cherry pie. There was another longest war in U.S. history. Poverty still prevails. Cities burn. And in spite of the hype, nothing really changed that summer. And if it did, it is best forgotten.

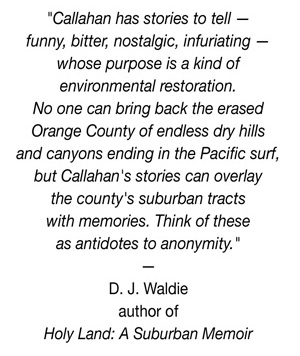

— Nathan Callahan