As a rule, our technology advances before we develop a capacity to cope with it. That’s why technological progress is painfully complicated. Sometimes the technology is a blessing, sometimes it’s a curse, sometimes it’s both — leaving many of us baffled by how to manage, if not survive, our latest creations.

Survival (or necessity) may be the mother of invention. But so is want. Unfortunately, we are driven by our own devices toward wanting everything. Yet, when our everything is loosed on the world, it never behaves as expected. Our inventions move serendipitously, as if they had minds of their own, all the while laying the foundations for our wars, our artistic movements, our fonts of financial wealth, and our revolutions in thinking. They vacuum our carpets, brush our teeth, shape our ethics, provide us with cures for all manner of disease, give us identity, then destroy us, never bothering to ask if we’re up to the challenge.

In Nicholas Ray’s 1955 generation gap border-line B-movie Rebel Without a Cause, James Dean’s existential Hollywood “bad boy” identity confronted that challenge and paid the price. Technology killed the movie star. Writing about Rebel in The New York Times, the often curmudgeonly, yet highly respected Bosley Crowther condemned Dean’s performance and the film as “violent, brutal and disturbing” decrying the “weird ways” of its youthful cast (further guaranteeing its ultimate success). Portraying Jim Stark, a suburban troubled teen, Dean dealt with with social rejection, knife fights, clueless cops, poor parenting, and friends who kill puppies. But Crowther’s puritanical review, was more than just a reproach of what he saw in Dean’s decadent Stark. A month before the film’s release, the star’s obsession with speed — and the technology behind it — gave the film a “violent, brutal and disturbing” boost. Breaking-in his Porsche 550 Spyder on his way to the 1st Annual Salinas Optimist Club Road Car Race, Dean was catapulted to his death in a head-on crash with a 1950 Ford coupe driven by a Cal Poly State University student named Donald Turnupseed. It was a death rich in allegory. Rebel Without a Cause’s promo said it all, “J. D. — Juvenile Delinquent… Just Dynamite… James Dean!” Warner Brothers had a hit. J.D. was Just Dead.

As allegory would have it, Dean’s pivotal scene in Rebel was a confrontation with human invention, and became not only a cinematic totem of mid-century modern teen angst, but supplied philosopher Bertrand Russell with a metaphor for the insanity of our Cold War Technology.

Here’s the setup: While trying to blend in with his high school student body, Stark (Dean) has a clash with a dim-witted bully named Buzz Gunderson. After a brief exchange of disinterest and sublimated jealousy, Buzz and his like-minded friends challenged Stark to a match against death called “Chicken.”

Chicken is a zero sum game. In real time with real people, it’s played by piloting your car at high speed on a straight road directly at another car and driver returning the favor. The first driver who thinks this is not such a good idea swerves out of the way becoming the loser, and in turn, a cowardly “Chicken.” A formal version of the game of Chicken has become the subject of serious research in game theory. But for our purposes, the winner is the one who harnesses technology while tempting death.

In it’s root form, Chicken was a game for transgressive suburbanites. But in Hollywood — in Rebel Without a Cause — Chicken became a game of applied existentialism — pitting Dean v Buzz racing their cars not at each other, but towards an abyss — in this case the edge of a cliff above the Pacific Ocean. As their cars sped toward oblivion, the first to jump out before sailing off the cliff would be a “Chicken”.

The pacing of Rebel Without a Cause‘s Chicken scene is pure teen-noir-vogue. Stark drags on his cigarette. Buzz slicks back his hair. All the high school midnight hipsters scope it out: Sal Mineo, Dennis Hopper, Natalie Wood, the usual suspects. They line up their cars — their technology — forming a vanishing point corridor that leads to the Pacific Ocean’s being and nothingness.

Natalie Wood, the embarrassingly beautiful brunette, who plays Buzz’s squeeze (while longing for a turn at Stark) is chosen as the starter. She seems to have done this sort of thing before, and, like a bouncy cheerleader of a teenage death cult, gleefully orders the spectators to turn on their headlights forming a Leni Riefenstahl-esque illuminated Beach Blanket Bingo gauntlet. Gentlemen start your engines. Buzz rakes his hair back. Stark checks his door.

And they’re off.

Buzz and Stark speed toward the cliff. Cut to Stark glancing at Buzz. Cut to Buzz glancing back. Stark flicks his cigarette. Buzz clamps the comb in his mouth like a pirate’s knife. There’s a beat. Then unexpectedly, Bonehead Buzz tangles his leather jacket in the car’s interior door handle. The technology traps him. He can’t open the door to escape. With his freewill all but gone, he shrieks. At the last second, in the other car hurdling toward oblivion, Stark jumps to safety. Both cars high dive off the cliff bursting in flames on the rocky shoreline below, Buzz — the winner — along for the ride.

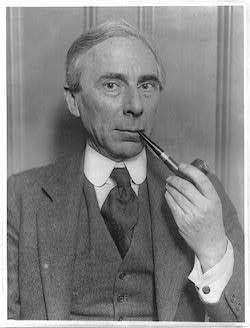

Coupled with Dean’s untimely death, Rebel Without a Cause gained an cult following with the disenfranchised rebel demographic, making the game of Chicken de riguer in low-budget “juvenile delinquent” movies. By 1959, the game caught the eye of 78 year-old British mathematician, pacifist, and Nobel prize-winning philosopher, Bertrand Russell. In it, he saw a metaphor for US-Soviet nuclear brinksmanship — the challenge of atomic technology.

The game may be played without misfortune a few times, but sooner or later it will come to be felt that loss of face is more dreadful than nuclear annihilation.

Bertrand Russell

“Since the nuclear stalemate became apparent,” Russell wrote in his book Common Sense and Nuclear Warfare, “the Governments of East and West have adopted the policy which Mr. Dulles calls ‘brinkmanship’. This is a policy adapted from a sport which, I am told, is practiced by some youthful degenerates. This sport is called ‘Chicken!'” Russell continues. “As played by irresponsible boys, this game is considered decadent and immoral, though only the lives of the players are risked. But when the game is played by eminent statesmen, who risk not only their own lives but those of many hundreds of millions of human beings, it is thought on both sides that the statesmen on one side are displaying a high degree of wisdom and courage, and only the statesmen on the other side are reprehensible. This, of course, is absurd. Both are to blame for playing such an incredibly dangerous game. The game may be played without misfortune a few times, but sooner or later it will come to be felt that loss of face is more dreadful than nuclear annihilation. The moment will come when neither side can face the derisive cry of ‘Chicken!’ from the other side. When that moment is come,” Russell concluded, “the statesmen of both sides will plunge the world into destruction.’

Since Russell’s pronouncement, the game of Chicken has been played by eminent statesmen in endless endtime scenarios: in the Cuban Missile Crisis; in the Yom Kippur War; in the Cold War; in Ukraine, in Gaza, and so on, and so on. But what’ s usually missing in any study of the “game” is the mischievous presence of a third player: a means to the end — the car, the bomb, the monster, the vehicle, the technology that pulls us into the abyss.

Buzz was a bonehead. But so was Stark, and so was Dean, and so are all of us; you, me, Dulles, Nixon, Khrushchev, McNamara, Powell, Reagan, Clinton, Bush, Obama, Trump, Biden, and so on, and so on.

Technology, on the other hand — in Dean’s case, the car — pays no attention to who we are, or our capacity to cope with it. And for better or worse, it now knows us intimately — the way we move and talk, the bed we make, the cloud we live in.

Racing into the future, accelerated by a technology moving exponentially faster than our understanding of it, we the feel the existential pull, the wake of air around us, the vacuum . We run a comb through our hair.

We may get our sleeve caught in the door handle.

We may jump clear.

We may plunge to our death.

But one thing is certain. We are all along for the ride, and, as a rule, we are unprepared for what our technology will bring.